The idea that running barefoot offers a metabolic advantage over running shod may be an “appeal to nature” fallacy.

Although some studies have found that running barefoot is actually “more efficient,” there have been a host of other studies that contradict those results.

So we can’t say for sure.

In a 2012 study titled Metabolic Cost of Running Barefoot Versus Shod: Is Lighter Better?, Franz et. al. set out to debunk the claim that barefoot is indeed more efficient. In a nutshell, their results found that not only did barefoot running have no metabolic advantage over running shod, but actually seemed to be more metabolically costly to do so. It has been suggested by several studies that the reason for this added metabolic cost is because of a “cost of cushioning.” According to these studies, the body is making an effort to absorb impact when running barefoot, that it doesn’t make when shod (more on this later).

I largely agree with the research question, experimental design, and results of Franz et. al. But reading this article stirred up several theoretical issues that don’t have much to do with the article in particular, but are important in terms of how the shod/unshod and hindfoot/forefoot striking debates have unfolded, particularly regarding what the terms “efficiency” and “better”—as in the title of the study mentioned above—have come to mean in this debate.

Franz et. al. begin the article by writing that “advocates of barefoot running claim that [barefoot running] is more “efficient” than running in shoes.”

First I’ll address the question of what we mean when we say “efficiency.”

It’s important to be clear that the advocates that Franz et. al. cite (Richards & Hollowell, authors of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Barefoot Running and Sandler & Lee, authors of Barefoot Running) are using the classical definition of “efficiency” as do Franz et. al.—meaning that they claim there is a lower energetic cost to barefoot running. That claim may well be a fallacy, and Franz et. al. are right to debunk it.

But I want to draw attention to a different use of “efficiency,” which will eventually get us to analyze what we mean when we say that one function (say, shod running) is better than another (say, barefoot running). In order to do this I need to bring in one of my favorite concepts from systems thinking: resilience.

One of the hallmarks of a resilient system is that it is built out of many tightly-coupled feedback loops, which basically mean that there is a lot of movement and interaction between its various parts. And for that movement to exist, the resilient system must be spending larger quantities of energy than the less-resilient system.

(This idea is rooted in thermodynamics: the movement of molecules and atoms correspond to the amount of energy stored in a certain space, i.e. the temperature of that space). The idea that greater movement can only be produced by a greater use of energy is generalizable to basically everything.

Note, however, that the causal relationship between resiliency and increased consumption of energy only goes one way: all other things being equal, a more resilient system must be using more energy than a less resilient one, but a system that uses more energy than another is not necessarily more resilient.

In the classical definition of “efficiency” that Franz et. al. and the barefoot running advocates are using, the resilient system is less efficient—i.e. it is at a metabolic disadvantage, since it uses more energy—than the non-resilient system. It isn’t very useful to speak in terms of “efficiency” when we’re talking about complex behaviors like athletic performance: for example, when the body finds itself in crisis, it will begin shutting down major organs to conserve energy. And for every organ that it shuts down, the less resilient it is: it becomes less and less able to cope with new and unexpected crises. Is this more “efficient” in any reasonable sense of the word but the classical? Not really.

“Efficiency” in the classical sense has never been the goal of human running. In Waterlogged, Tim Noakes explains how running on two legs has a much greater metabolic cost, across the same distance, than running on four legs, and yet, because humans run on two legs, we are capable of running down antelope and other ungulates in the desert. (The advantages that running on two legs offers are thermodynamic, but that’s a story for another time).

Simply stated, if efficiency was what the human body wanted in the first place, we would have never gotten off all fours. Actually, we would never have become runners at all. But we did. So there has to be more to this story. By standing on two feet, there has to be another problem that we were trying to solve beyond “efficiency.” That problem is most likely how to be resilient in the performance of particular function: human endurance running.

The human body—like any system—has other goals beyond pure efficiency. Indeed, one of the primary goals of the human body is redundancy. Studies have shown that even when we exercise at maximal intensity, only a fraction of our sum total muscle fibers are recruited. In the classical sense of “efficiency,” you could say that it is less efficient to be redundant, since more energy and nutrients must be spent building these redundancies instead of using them for athletic performance.

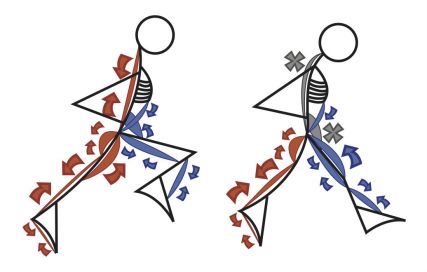

All of this gets us to what we mean when we say “better.” In a very real way, (and for a variety of reasons), it isn’t “better” for the human body to be “more efficient” in the classical sense. It’s better for the body to be more redundant, and more resilient. In theoretical systemic terms, the fact that the number of active “feedback loops” increase when running barefoot—since the touch receptors on the soles of our feet “feed back” information to our muscular system, which works to decrease impact—is indicative of the likelihood that the unshod system is more resilient than the shod system.

Furthermore, when we blow up the term “efficiency” onto the large scale (divorcing it from its classical meaning), we can ask ourselves: in time and energy, what are the advantages of protecting the system, over not doing so? According to the literature, wearing shoes doesn’t protect the system in its entirety, beyond the skin on the sole of the foot: It has been shown consistently that shoe cushioning doesn’t affect peak impact force, only our perception of that impact. Peak impact force is alleged to be the main cause of repetitive stress injury in runners. While it has also been shown that in hindfoot-striking, shoe cushioning decreases loading on tissues), loading is a very different issue, with different consequences to injury, than impact.

Given that running shod reduces the activity of our cushioning mechanism, it would be extremely informative to do a long-term study on the amount of impact absorbed by the tissue (as opposed to loading), when the cushioning mechanism is deactivated. (Short-term studies already provide evidence that impact forces are indeed reduced when running barefoot as opposed to running shod). In turn, it should be explored how the increased impact translates to tissue damage, recovery time, and ultimately time not spent developing athletically.

In these terms, we may yet discover that it is more “efficient” for the body to run barefoot than shod. Being this the case, we could say that it is “better” for the system to run barefoot than shod.

Whether this is actually the case remains to be seen. What we can do at this point is to observe how our words shape our perception, attention, and inquiry, and what it is that systemic insights can bring to the table, both theoretically and with an eye towards future experimental research.