The term “heel-striking” shouldn’t just refer to which part of the foot hits the ground first. Even in the common parlance, it should refer to the collection of neuromuscular gait features across the body that contribute to a type of overstriding in which the heel lands first, ahead of the center of gravity.

When I write the words “heel-striking,” this is invariably what I mean.

This way, we can neatly sidestep the conversation of whether someone landed on their heel under their center of gravity, or only “appears” to heel-strike. Let’s do away with reductionist analyses: let’s make it about something else than just “the strike.” The most widespread way in which the western runner overstrides is by heel-striking.

In a previous post, I reviewed how there is a paradigmatic body geometry to midfoot-striking, which corresponds to a paradigmatic pattern of muscle use. Heel-striking is no different.

When I say “paradigmatic,” I refer to the core components of the stride; to its most generalizable features. For example, the paradigmatic body geometry of midfoot-striking consists of a full-body arch, which begins at the base of the head and ends at the heel.

Establishing the paradigmatic features of types of running strides allows us to observe those features and make reasonable predictions about them. If you look at a runner who appears to be heel-striking, and yet is creating a full-body arch starting from the base of the head and ending at the pushoff heel, you can be reasonably certain that if you look closer, you will actually find this runner to be midfoot-striking. In other words, you can know that Meb Keflezighi’s apparent heel-strike (left), is actually a “proprioceptive heel-strike”—rather, a “disguised” midfoot-strike—just by looking at the continuous arch made by his leg and back at pushoff. (This video makes my point rather well). You may notice that other noted forefoot-strikers create very similar arches:

Because every person has a slightly different body geometry, the specifics of their stride will be slightly different. But these specifics are much more similar to each other than it is usually claimed. For example, in the post previously mentioned I reviewed how, necessarily, for all humans, dynamic strength is necessarily achieved by creating a series of consistent and symmetrical arches with the body’s bone structure. The reason this applies to all humans is because it applies to all structures. The integrity of every possible structure—from the Hagia Sophia to the plantar vault—is subject to the symmetry and consistency of its arches.

From this idea, we can extrapolate that no human can be the strongest version of themselves without creating the most consistent and symmetric arches across the body. Therefore, when you look at the differences betwen midfoot-striking and heel-striking, the differences in body geometry stand out starkly: unlike midfoot-striking, heel-striking paradigmatically breaks the full-body arch that makes the midfoot-striking body so resilient.

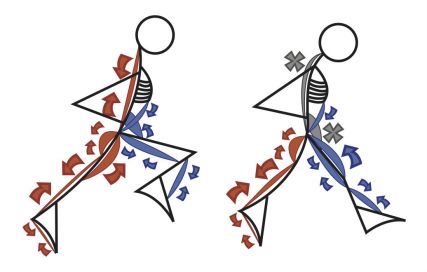

There may be a few runners out there for whom a true heel-strike doesn’t break this full-body arch. There may even be others who can land on their heels, under the center of gravity, without breaking this arch. But paradigmatically, the stride difference between forefoot-strikers (left) and heel-strikers (right) looks like this:

As mentioned before, a paradigmatic body geometry corresponds to a particular pattern of muscle use. In the above graphic, you can observe major differences between midfoot-striking and heel-striking in the neuromuscular paradigm of both the extensor muscles used during pushoff (red) and the flexor muscles used during the swing phase (blue). Of course these two types of body geometry load different tissues in different ways. That’s the point.

The most important differences are (1) the reduced iliopsoas function for the heel-striker (depicted by a grayed out X at the hip), (2) the reduced function of the upper back extensors (grayed-out X at the back), and the concentric activation of the quadriceps muscle for the heel-striker (blue arrow at the thigh).

The heel-strikers’s upper leg is in a bit of a predicament: during the swing phase, both the quadriceps (front thigh muscle, blue), and the hamstring (back thigh muscle, blue) are active at the same time. This is a problem because, when the leg is forwards of the hip, the hamstring flexes the knee, while the quadriceps extends it. This means that two muscles of the body which perform opposite functions are active at the same time, pulling in opposite directions. And this is happening as the leg is nearing the ground—during the landing phase—which means that two of the major muscles of the body are fighting each other, and they are doing so at the very moment that the body is about to slam into the ground.

This isn’t a problem for the midfoot-striker: the fact that the front knee is bent, and near the height of the hips, means that the quadriceps is largely inactive at that stage. Full quadriceps activation only occurs towards the end of the pushoff phase (front thigh muscle, red).

Because athletic power is generated through the creation of consistent and symmetric arches, any running body will always be the most powerful version of itself as a midfoot-striker. Furthermore, the body is designed around these principles: because load-bearing structure (the arch) is most consistent when the body is powerfully midfoot-striking, the body is at the peak of structural resilience when midfoot striking. Given that resilience is a hallmark of systemic integrity, this means that a systemic analysis of the body can only basically conclude that the human biomechanical system is operating at its “peak” when it is midfoot striking.

Similarly to the heel-strike, the midfoot-strike doesn’t refer to the part of the foot that hits the ground first. It refers to the constellation of stride components (such as the creation of a full body arch), that allows this part of the foot to hit the ground first.

This post shouldn’t be construed to mean that we should ONLY midfoot-strike. There may be plenty of reasons to heel-strike, such as rapid deceleration, and the opportunity to use the heel bone as a swivel, in order to turn quickly. However, for the purpose of producing safe and sustained forward motion, no type of stride will yield results that are as consistent or as powerful as those allowed by the midfoot-strike.